A praxis toward reckoning

|

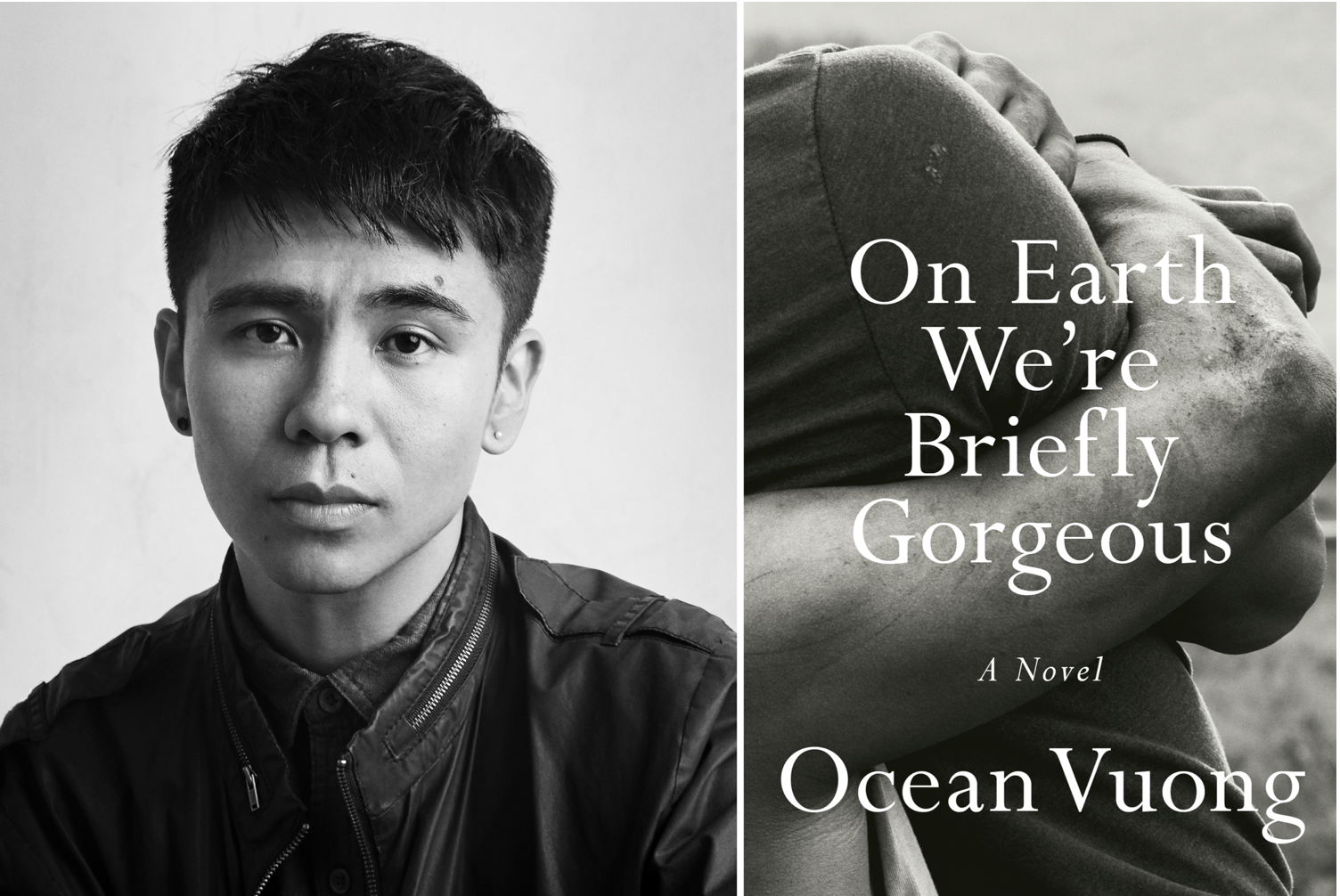

| Paris Review (Author Photo: Tom Hines) |

Two articles with/by Ocean Vuong in the Paris Review last year. Read them this morning. Thinking about these topics in my own life.

Survival as a Creative Force: An Interview with Ocean Vuong

By Spencer QuongParis Review June 5, 2019

INTERVIEWER

Little Dog says, “I am writing you from inside a body that used to be yours. Which is to say, I am writing as a son.” There’s both intimacy and distance here: “used to be.” I imagine it’s not always clear how exactly our family’s voices arrive—or fail to arrive—in our work. How have you balanced your family’s voices with your own?

OCEAN VUONG

I wanted the book to be founded in truth but realized by the imagination. I wanted to begin as a historian and end as an artist. And I needed the novel to be a praxis toward that reckoning.

This book is as much a coming-of-age story as it is a coming-of-art. I would say that I begin with the voices of those I care for, family or otherwise, and follow them until they drop off, until I have to create them in order to hear them. My writing is an echo. In this way, On Earth is not so much a novel, but the ghost of a novel. That’s the hope anyway.

...

The gaze, human or animal, is a powerful thing. When we look at something, we decide to fill our entire existence, however briefly, with that very thing. To fill your whole world with a person, if only for a few seconds, is a potent act. And it can be a dangerous one. Sometimes we are not seen enough, and other times we are seen too thoroughly, we can be exposed, seen through, even devoured. Hunters examine their prey obsessively in order to kill it. The line between desire and elimination, to me, can be so small. But that is who we are. There must be some beauty—and if not beauty, meaning—in that brutal power. I am still trying, and mostly failing, to find it.

...

One question this novel hovers over is how do people who hurt each other find ways to protect themselves while attempting to love and, ultimately, to heal? I think Little Dog learns that to experiment is to innovate—and to innovate is to live in hope. Innovation is the first casualty of cynicism. The characters in this novel test each other because they possess an optimism that outlasts their hurt. And I adore them for that.

...

“I thought sex was to breach new ground, despite terror, that as long as the world did not see us, its rules did not apply. But I was wrong. The rules, they were already inside us.”

I wanted to arrive at queer joy—but discovered that I wanted to do so without forsaking the very real and perennial presence of danger that queer bodies face simply by existing. There is a call, rightfully, for literature to make more room for queer joy, or perhaps even more radically, queer okayness. But I did not want to answer that call by creating a false utopia—because safety is still rare and foreign to the experiences of the queer folks I love, who are also often poor and underserved. I didn’t want to pretend to be happy just because straight people were tired or bored of our struggle.

The novel insists that there is power, and with it, agency, in survival—which includes the interracial tensions you speak of—because trauma is still an integral reality for queer folks. But these bodies do know joy, and they know it by acknowledging and honoring the tribulations they outlived. We often think of survival as something that merely happens to us, that we are perhaps lucky to have. But I like to think of survival as a result of active self-knowledge, and even more so, a creative force.

...

“We were exchanging truths, which is to say, we were cutting one another.”

...

INTERVIEWER

I remember listening to you read at the University of Massachusetts a number of years ago when Night Sky was released. I remember the quiet of that room, the ways your pauses swept over the audience. I’m curious about how it feels to you when you read your work aloud.

VUONG

You were there! That makes me retroactively happy. I was so nervous that night, but someone had the merciful idea to turn off the lights. And I grew braver in the dark, which became somehow more intimate, less lonely. I’m not really a social person. I’m naturally shy and avoid parties when I can. ... So I never dreamed of being a reader in front of an audience. But when I started to do it, I realized I was participating in an ancient oral tradition, one that made not only Vietnamese literature possible, but solidified the practice of storytelling in our species. I started to see the air as a second page. The book, any book, as you encounter it between two covers, is essentially a fossil.

...

I’m not interested in possession. I want to be freer than that. Maybe I’m being naive, but I understand genres to be as fluid as genders. Our lives are full of restrictions—jobs, bills, time, gravity, all of this impinging on us—but to write is to gift yourself the freedom of choice and possibility. That feels truly precious to me.

If we must think in metaphoric structures, then I would rather say the novel is a town square—a space where people converge, where they’ll see these characters, see me, see each other, then go on home, perfect just as they are.

Reimagining Masculinity

By Ocean VuongParis Review June 10, 2019

No homo.

You’re really good at hiding.

Years later, in another life, before giving a reading, the organizer asked me for my preferred pronouns. I never knew I had a choice.

Can the walls of masculinity, set up so long ago through decrees of death and conquest, be breached, broken, recast—even healed? I am, in other words, invested in troubling he-ness. I want to complicate, expand, and change it by being inside it.

No homo, K reminds me, as he bites off the medical tape, rubs the length of my swollen ankle. He slides my white Vans back on—but not before carefully loosening the shoelaces, making room for my new damage. No homo, he had said. But all I heard, all I still hear, is No human. How can we not ask masculinity to change when, within it, we have become so wounded?

“You’ll be fine,” he says—with a tenderness so rare it felt stolen from a place far inside him. I reach for his hand.

I make it so dark we could be anything, even more than what we were born into.

We could be human.

No comments:

Post a Comment