Teju Cole - Go Down Moses

Questions of liberation tend to interleave the present and the past. What is happening now is instinctively assessed with the help of what happened before, and both despair and hope are tutored by memory. The old Negro spiritual “Go Down Moses,” beloved by Harriet Tubman and generations since, sought to link the black American freedom quest with the story of ancient Israel’s struggle to be free of Pharaoh’s bondage.

Humanity is on the move. The ground beneath our feet is shifting, the skies cannot be relied upon, and even our own bodies bear the marks of the strain. Everyone is longing to be free, and everyone is curious about whether hope is still possible. The photographic archive contains evidence that thus it ever was, that we have always lived in this urgency.

Through an intuitive sequence of photographs, in images soft and loud, this exhibition proposes a redefinition: that hope has nothing to do with mood or objective facts, but is rather a form of hospitality offered by those who are tired to those who are exhausted.

Teju Cole, Curator's Statement

Go Down Moses - Museum of Contemporary Photography - July 18 - September 29, 2019

The Ground Beneath My Feet Is Shifting

Teju Cole puts the interplay of despair and hope at the center of the exhibit, that is the story he is telling with photographs from the archive of the Museum of Contemporary Photography. I am repeatedly drawn back to the opening statement, as much as to my memory of the exhibit and the book from Candor Arts.

Change is the only constant. I pretend that the present is stable and the future will be like the parts of the past that support the stories I tell. The truth is that the story is much bigger than what I wish it would be. It is a past and present filled with pain, suffering, and systemic inequities. Inequities which have fueled wars, genocides, mass incarcerations, and dynamics which further entrench the elites. It is also a past and present filled with love, compassion, soaring art and spiritual wholeness. There are examples of old wrongs righted, of increased equity, of more voices joining the conversation and a broadening of the distribution of power.

A Redefinition of Hope: Hospitality

Initially, I was taken by the closing paragraph: a redefinition of hope. I need to be reminded of that, that hope is a form of hospitality. It's not that I am hopeful for myself or for an outcome, but that I can offer support to those who are exhausted. A sip of water on a hot day. A few moments of respite. While there is much work to do, hope is about connecting through acknowledgement, through witnessing, through being present and available.

We have always lived in this urgency

As I read the first two paragraphs more closely, they speak to me of the archive as a tool to "interleave the present and the past".

The declaration that "humanity is on the move" and that this is the human condition, to be on the move. Our sense of place, even our being in our own bodies, is undercut by change, by challenges to any fixed way of being. It is this challenges to our complacency, to our usual way of being, which forces change, forces maturity.

Life is fragile. It is precious. It is sacred. We can live in the urgency of the moment. We always have.

My Archive

I am drawn to my personal history, my personal archive, my personal collection of photographs, my telling of my life. I'm also searching the broader cultural archive (for example, Sachsenhausen December 1938). I'm discovering, again and again, how my understanding of myself, my own story, and that of society as a whole, was shaped by a limited knowing, by single threads and single perspectives.

My story as an American, as a grandchild of immigrants, as a Jew, as a homosexual, as a white professional, is a story of being Other and being Privileged, a story of the tsunamis of the past which have drowned us and the cresting waves that have lifted up.

I'm working to combine some of these threads in this project, creating portraits from the faces in the Sachsenhausen photograph.

Let My People Go

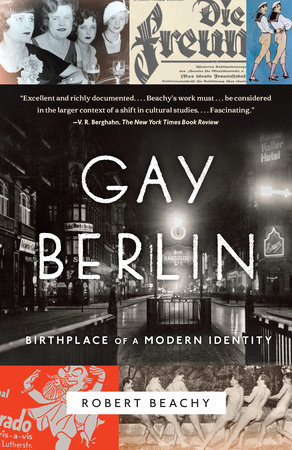

Coming to the title of the exhibit, Go Down Moses, the old Negro spiritual. A coded and fully visible cry for freedom. A link across time into our collective past, through various slaveries, in different cultures. The American enslavement of Africans. The enslavement of the Israelites. There are many ways we each navigate the available space to be visibly ourselves, to acknowledge what makes us different, to declare our presence, and to adopt forms which do not trigger aggression against us. And to offer our voices in hospitality.

The Spiritual

An artist friend suggested these three YouTube versions of “Go Down Moses”. Here are her comments:

Earlier Comments on this Exhibit

I blogged about the Go Down Moses exhibit on August 19, 2019, That post also discusses a conversation between Teju Cole and Dawoud Bey.